Explore Our Network of Sites

Search

By:

In the tech boomtown of Austin, data is king — and city staffers are making some of the country’s strongest data-driven arguments for better bike infrastructure.

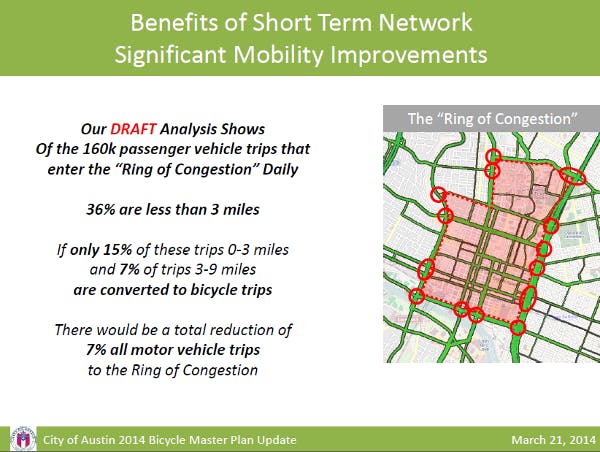

A new slideshow by Austin engineer Nathan Wilkes spells out the virtues of a $140 million protected bike lane network that would, he and colleagues calculate, increase the street capacity of Austin’s congested central business district by 7 percent.

Wilkes says that’s the sort of analysis needed for a shift away from thinking about bike projects one street at a time and toward thinking about networks.

“Isolated protected facilities are like coming up for air,” Wilkes writes. “But only when facilities and networks are cohesive will we see big change.”

Networks are already bringing big change to auto-jammed cities like Seville, Spain, where the citywide share of trips by bike leapt from 0.5 percent in 2006 to 7 percent in 2012 after the city added a bike sharing system and a full network of protected bike lanes. That’s the thinking behind our four favorite slides in Wilkes’ slideshow about the plan, which should serve as a mini-education for government leaders across the country in ways to think about and measure the many benefits of bikeways.

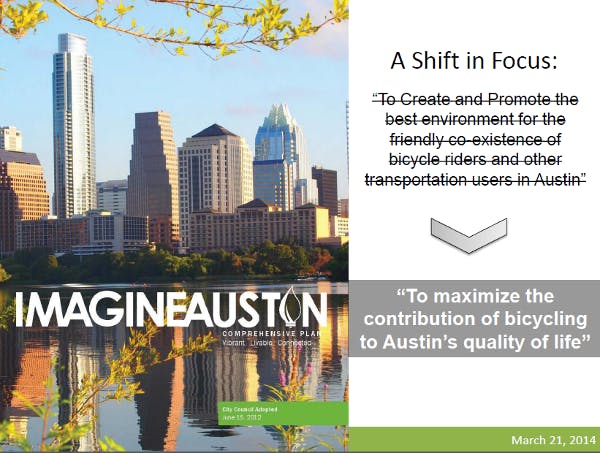

Here’s the former mission statement for Austin’s bike plan, followed by its new one:

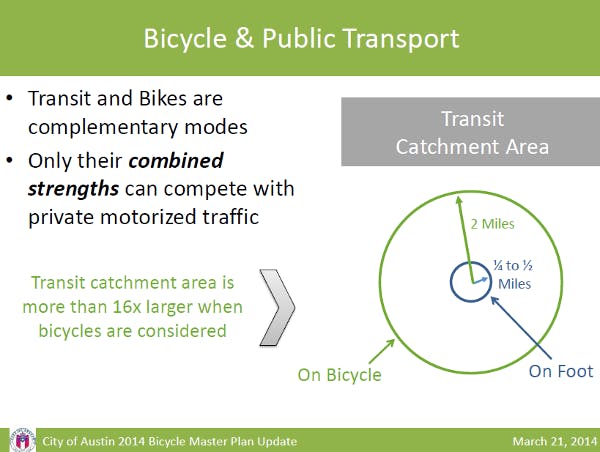

What’s the single biggest problem with public transit, especially in U.S. cities? The time it takes to walk to a stop that has decent bus or rail service. Biking solves this problem, greatly increasing the population that can be served by a single high-quality transit line — as well as the number of fares a single station can generate. This isn’t to say that transit lines shouldn’t run to all neighborhoods. What good bike access does is increase the payoff of any given station.

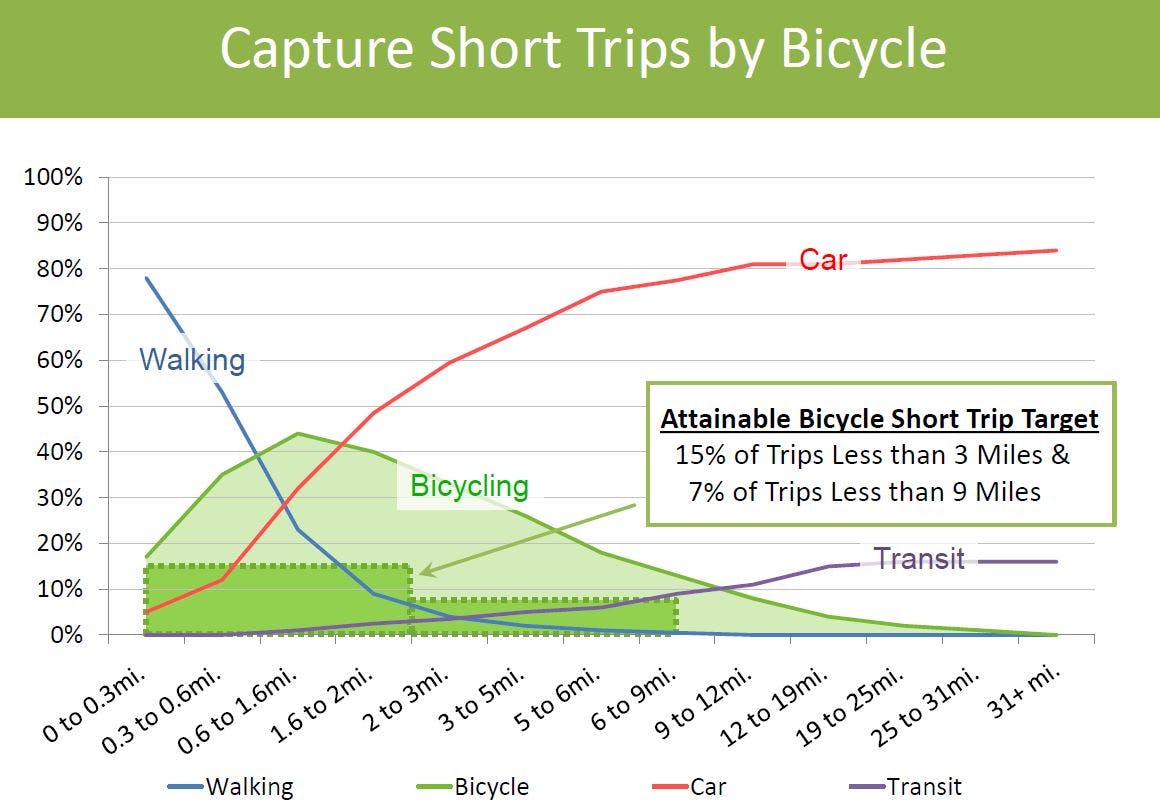

When people have comfortable options for every mode of travel, they naturally choose the right vehicle for the right trip. Wilkes used actual behavior patterns from the Netherlands to make this chart of “attainable” targets for Austin if it has a comfortable biking network where people currently take many short trips. Austin’s draft analysis estimates that a protected bike lane network would make bikes the vehicle of choice for 15 percent of trips under three miles and 7 percent of 3-9 mile trips, far below nationwide levels in the Netherlands (pictured).

The really groundbreaking thing about Austin’s current bike planning is that it expresses the benefits of biking largely in the language of engineers: it looks at bikes as a way to increase the number of trips a congested road system can carry.

And it’s very persuasive.