Explore Our Network of Sites

Search

By:

It was 2012, and Leah Golby was sitting in a meeting she’d been looking forward to for three years.

A recently elected city councilor for the 10th Ward of Albany, N.Y., Golby had heard years of lobbying from 10th Ward residents for a redesign of Madison Avenue, a four-lane thoroughfare just south of downtown. Albany was finally holding a work session about a road diet for the street.

But as the project consultants ran through the new profile — turn lane, travel lane, bike lane, parking lane, sidewalk — Golby raised her hand. Why not put the lanes in the other order, she wanted to know: travel lane, parking lane, bike lane, sidewalk?

Golby didn’t have a name to the concept. She only knew that she’d seen it recently in New York City, and that it had made riding a bike through Manhattan seem, for the first time, safe.

Her question was dismissed immediately, she said.

In the four years since we launched in late 2012, we’ve told hundreds of remarkable stories on the Green Lane Project blog about the spread of protected bike lanes across North America, from Atlanta to Lincoln to Honolulu ? all of it driven by heroic change agents at the local level.

But one remarkable story we’ve never told is the story of the Green Lane Project itself: a small squad assigned the task of taking a simple but unfamiliar concept — protected bike lanes — and transforming it from an oddball European practice used by one or two U.S. cities into a widely embraced tool, familiar to hundreds of thousands of Americans and on the way to being embraced and standardized by the country’s biggest transportation institutions, within a few years.

This is the story of how that happened.

First, we’ll send some fan mail: The Green Lane Project team was definitely not the only set of people who drove this shift. We’ve stood on the shoulders of giants, like prescient academics Anne Lusk and John Pucher; we’ve walked in the footsteps of visionaries, like transportation commissioners Janette Sadik-Khan and Gabe Klein. We’ve moved in tandem with allies from NACTO to Streetsblog.

But the Green Lane Project’s strategy has never been to become legendary itself. You can’t simply decide to be a giant or a visionary, after all.

Instead, its approach to change has been more unusual: make a few tiny tweaks to American transportation policy, almost invisible from a distance, that would quietly create circumstances in which local visionaries could successfully change American city streets.

And, more importantly, to eventually create circumstances where visionaries will no longer be required to make change happen.

It was 2011, and Martha Roskowski was restless.

An accidental bureaucrat with a journalism degree and a goofily wide grin, Roskowski was in the middle of an unusual career in an unusual field: bicycling advocacy. Nine years earlier, after winding her way from freelance video production to running Bike Week for the City of Boulder to becoming the executive director of Bicycle Colorado, Roskowski had landed in Washington D.C. in 2002 with a very specific assignment: get the next federal transportation bill to accommodate bicyclists and pedestrians in every project it funded.

The concept was called “routine accommodations.” The idea had been around for years, but nobody seemed excited about it.

“It’s a lousy name but a great concept,” Roskowski recalled. “I was like, OK, it’s a lousy name. What if we give it a better name?”

Roskowski hired a communications pro named Barbara McCann, called up the smartest people they knew, bought some cheap pizza and gathered them all in the conference room of the League of American Bicyclists to brainstorm a better name.

That afternoon, they walked out with a new phrase: “complete streets.”

The concept didn’t end up in that federal transportation bill. But the new name for streets with sidewalks and bike lanes flipped a switch in a million brains. Of course streets ought to be complete. Of course bike lanes ought to be standard.

McCann went on to create and lead the National Complete Streets Coalition, which has since seen 850 agencies around the country adopt Complete Streets ordinances. Roskowski, meanwhile, moved back to Boulder, took a job with the city’s transportation division and started raising a family.

In 2011, Roskowski had been at the city for seven years, and her feet were getting itchy.

“I seem to do things in seven-year cycles,” Roskowski said. She wanted to try introducing another good idea into the U.S. transportation world. But what?

The answer would come on a long walk with an old friend.

Randy Neufeld had started his career as a curly-haired political organizer in Harold Washington’s Chicago. Some time in the mid 80s, poking around for a specialty, he decided he wanted to do some sort of activism that was not too big and not too small.

“I was looking for something between world peace and homeless shelters,” Neufeld says now.

He settled on bicycling.

Reed-thin and over six feet tall, Neufeld had scorned bike lanes as unnecessary even after he became the first executive director of the Chicagoland Bicycle Federation in 1987. Then, in 1993, Chicago striped its first bike lanes on Wells Street. Neufeld was amazed to watch as people gravitated to the route on bikes.

Bike lanes worked, he decided, because they were “huge billboards all over the street that this was a bicycling place.”

Neufeld and Roskowski first met in 1996 in the Denver airport, both in their mid-30s and both on their way to a meeting that would transform American biking advocacy forever. U.S. cities had recently reversed their long economic decline, and something interesting was happening in response: new local biking and walking advocacy groups were popping up in one place after another, led by youngish professionals like Roskowski and Neufeld.

Now, the Bicycle Federation of America had invited 25 of those state and local leaders to meet for the first time at the Thunderhead ranch in western Wyoming. That week’s summit would mark a turning point for much of the American biking movement: a transition from technical grousing to systemic change.

Also at that Thunderhead retreat was one of the movement’s most charismatic strategists, 30-year-old Susie Stephens of the Bicycle Alliance of Washington. She would introduce Neufeld and Roskowski to a set of ideas that would shape their work for decades: a theory of how innovative ideas spread.

Some ideas are better than others. But not every good new idea catches on.

Under the theory championed by Stephens — originally developed by Everett Rogers and further explained by Alan AtKisson — any good idea starts with a rogue actor, trying something unusual and discovering that it works.

But discovery isn’t enough. For an idea to survive and thrive, it needs a few other people or organizations to adopt the innovation, to demonstrate that the first success wasn’t a fluke.

This moment, which can last for months or years, is the most delicate phase in the life of an idea.

Will the hatchling find its own worms? Will the first generation of seeds take root? Will the trickle of water find a way through the rock?

According to Rogers, an idea that gets enough momentum during this phase — embraced by about 15 percent of the relevant people — has made it. After that, mainstream status is only a matter of time.

In 2011, Roskowski and Neufeld reunited at Thunderhead for the 15th anniversary of the first summit. Neufeld was two years into a job with the SRAM Cycling Fund, tasked with spending $10 million over five years to make enduring changes to American biking.

“We went for a walk into these fabulous sagebrush hills,” recalled Roskowski. “I was telling Randy I was thinking about what I wanted to do next. I said, ‘I’ve been thinking about protected bike lanes.’ He said, ‘I’ve been thinking about protected bike lanes.'”

The most interesting idea in the biking world at the time had taken root in the most unique city in the country: New York. Under Mayor Michael Bloomberg, the city was doing something that U.S. biking advocates had dreamed of for years: installing physical separation between cars and bikes, right on the street, complete with green coloring and special bike signals.

And it was working. In the last four years, the city’s bike counts had doubled.

Roskowski and Neufeld had been watching all this, wondering if the long-awaited idea would spread to other U.S. cities. As they walked through the Wyoming hills, the pair hatched a plan:It ought to be possible to use the ideas they’d learned from Stephens, years before, to help this idea along — to make it easier for the delicate new concept to reach its 15 percent tipping point and go mainstream.

Their theory of change was itself an unusual idea. Instead of trying to persuade the U.S. government to reroute the river of U.S. street design, they were just going to move a few pebbles.

But if they chose the right pebbles, the river itself would do the rest.

They headed home and started scheming.

Within months, the first pebbles were chosen.

PeopleForBikes, a national biking coalition based in Boulder, had loved the idea. In January 2012, the organization went in with Neufeld’s SRAM to give Roskowski a staff of two and a budget to choose six “focus cities” that were poised to bring New York City’s innovation one step closer to the mainstream.

Roskowski called the PeopleForBikes Green Lane Project “a gifted and talented program for cities.”

“In bike advocacy, we’ve spent years trying to win over the people who weren’t interested in changing,” Roskowski said. “With the Green Lane Project, we decided to find the people who did want change and help them do it.”

The Green Lane Project didn’t have enough money to pay for protected bike lanes itself. Only the cities themselves did. So Roskowski’s team had to somehow keep its leading cities excited enough about this type of infrastructure that they would shoulder through the inevitable opposition and build it with their own money.

This was Roskowski and Neufeld’s plan for doing it:

The first six focus cities were Austin, Chicago, Memphis, Portland, San Francisco and Washington. Roskowski and the Green Lane team went to work.

Everyone in Austin talked about traffic, but nobody seemed to be doing anything about it.

By 2012, Austin was the anchor of the country’s fastest-growing regional economy, and its streets showed it. The city had spent years debating light rail plans and costly freeway expansions. Meanwhile, the downtown that had been laying the city’s golden eggs was clogged with more cars every day.

When the city applied for Green Lane Project status in 2012, some city leaders had a vague sense that bikes might be part of the answer. But it wasn’t until October of that year that the city began to see bike lanes in a new way: mathematically.

The breakthrough came at a workshop by the Dutch Cycling Embassy, an organization the Green Lane Project had partnered with to connect cities with European expertise.

“They chose Austin to be a Think Bike workshop recipient, probably because of our affiliation with Green Lane, I’m sure,” said Annick Beaudet, the city’s former bicycle program manager.

At the workshop, a team of Dutch engineers led by Richard ter Avest presented an argument that, Beaudet and others said, has since transformed the way influential Austinites think about bicycling.

Instead of trying to boost biking mostly by pouring hundreds of millions into new bike trails and bridges in suburban areas, ter Avest said, Austin could also rearrange space on existing streets and get perhaps 20 percent of its short urban trips (three miles or fewer) onto bikes.

If that happened, a low-stress protected bike lane network would actually add the capacity for a million more trips each week on Austin’s most congested streets — all without knocking down a single building.

“It seemed sort of stunningly obvious,” said city consultant Jana McCann. But until then, no one in Austin had thought about bikes in quite that way. “Even the chamber of commerce and TexDOT were all at the table, like, Wow, all of this really makes sense.”

Austin had recently finished a new bike plan. But after its first year with the Green Lane Project, the city rewrote it to focus on protected bike lanes and short trips. Today, the city has installed eight miles of protected bike lanes and has added more than 100 miles to its plans.

When John Cameron was named city engineer of Memphis, Tennessee, he was like many residents in a city with zero bike lanes: he hadn’t used a bicycle in years.

“There were no good, what I perceived as ‘safe,’ roadways to ride on,” Cameron recalls.

In a city like Memphis, built largely on wide-open spaces, so many things were so far apart that Cameron found it hard to even imagine how biking could be practical. In that, it was much like the city’s bus system.

“They can’t run routes to the areas where there might be some demand — the density is so low that there aren’t enough people for it to be viable,” Cameron said.

But after Memphis was named a Green Lane Project focus city in 2012, Cameron joined a study tour of the Netherlands with other Memphis officials. And one day in a Dutch suburb, something clicked.

“The regional rail integrated with the bicycling facilities,” Cameron said. “It made perfect sense, after I’d seen that in person — how it made sense to commute to work using a bicycle to the rail station.”

The path to better biking in Memphis, Cameron realized, was also the path to better public transit.

“If we could develop safe, comfortable bike routes that would connect folks to the transit system, it would make another very viable transportation option for our citizens,” Cameron said.

After what he called his “aha moment,” Cameron returned to Tennessee a convert. In Cameron’s first four years, the city installed 71 miles of bike infrastructure and created “MEMFix,” a nationally celebrated model for community-driven street experiments with protected bike lanes and similar projects.

In the city’s most ambitious test, it converted half of a divided roadway along the Mississippi to a one-mile protected bike lane and walking path. A blog post about the project went viral among biking advocates around the country.

“Everything about this is perfect,” Brock Howell, policy manager for the Cascade Bicycle Club in Seattle, wrote beneath the post. “Just perfect. Memphis inspires Seattle.”

That plan’s champion had been Cameron.

Amid their work with the six focus cities, the Green Lane team also began working on a bike infrastructure moon shot.

They called it Project I, for “institutionalization.”

The mission: get protected bike lanes and signals written into the two Bible-sized documents that dictate almost all of U.S. roadway design — the Manual of Uniform Traffic Control Devices and the bike guide by the American Association of State Highway Transportation Officials.

Once advanced bike infrastructure had been written into those documents, Roskowski believed, barriers to better bike lanes would fall across the country. Engineers in cities of every size would be able to flip to a page in their book and get federally approved instructions on everything from lane width to signal syncopation.

But there was another option, too: get the federal government to formally endorse different guides that already included advanced infrastructure.

With the MUTCD and AASHTO guide showing little sign of rapid change, Roskowski began drawing up a plan to get the Federal Highway Administration to endorse an alternative document, the bikeway guide of the National Association of City Transportation Officials.

First, she circulated a poll to 107 city engineers, planners and consultants, asking whether a federal endorsement of NACTO’s guide would be useful to them. Ninety percent said it would.

Armed with that data, Roskowski started doing slide presentations around the country. One of those landed her an invitation to meet with the Federal Highway Administration to pitch them on endorsing the innovative new designs.

The session, Neufeld later recalled, was “one of the most fun meetings I had ever been at.”

They’d tipped Deputy Transportation Secretary John Porcari in advance what Roskowski was going to ask for, Neufeld said. So when the pitch for FHWA endorsment came, Porcari turned immediately to the front-line employees in the room.

“Porcari basically asked them if they could do this, and they said something like ‘Well, we’d have to ask AASHTO what they thought,'” Neufeld recalled. “And then he said something like ‘Couldn’t we do this without AASHTO?’ — And there was sort of a sheepish, ‘Yes, I guess we could.'”

“It was so beautiful to watch,” Neufeld said. “I wish I had it on video.”

Within weeks, the dominoes started falling.

At the end of July 2013, the FHWA issued a task order proposal request that would eventually lead to an official federal guide to building separated bike lanes.

The next month, another milestone: the FHWA issued a memo formally endorsing the NACTO guide and another document, the Institute of Traffic Engineers’ “Separated Bikeways” report, as valid design references alongside the MUTCD and AASHTO guide.

In July 2014, after years of slow action on new bike infrastructure, the MUTCD’s advisory committee passed a flurry of recommendations that amounted, in the words of committee member Peter Koonce, to “approving half the things in the NACTO guide.” Koonce, a traffic engineer for the City of Portland and longtime advocate for MUTCD changes, called it a “miracle meeting” and credited Roskowski’s work.

And in January 2015, AASHTO released a notice of its own, signaling that it was accelerating the process for rewriting its bike guide and suggesting that the time might have come for it, too, to endorse protected bike lanes.

Watching from Austin as it all happened, Beaudet said it felt like living through a “golden age.”

“There was this rich conversation,” she said. “New tools were just coming about so quickly.”

Within Austin’s government, she said, there was a sense of excitement and direction, like a wind blowing at their backs.

“It was like, ‘All hands on deck,'” Beaudet said. “We’ve got to do better with bicycle infrastructure. All hands on deck.'”

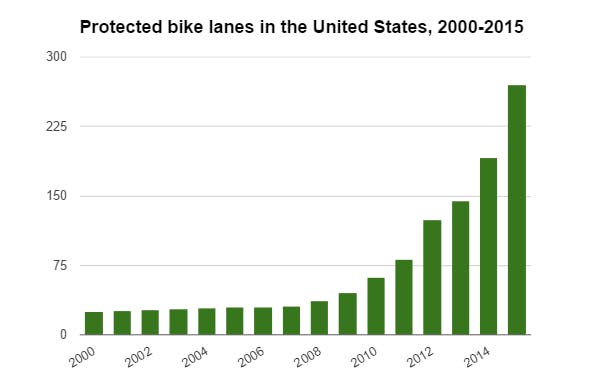

Today, four years after the Green Lane Project launched, the United States has 270 protected bike lanes in 82 cities, a figure that has literally been growing exponentially, doubling every 26 months.

Hundreds more are currently in progress.

In 2011, protected bike lanes were mentioned in the text of all U.S. newspapers once or twice a month. By 2015, the phrase was showing up somewhere in the country seven or eight times every week.

“We chose the right issue at the right time,” Roskowski said. “If we had tried to do this project 10 years ago, we would have failed miserably.”

But thanks to Lusk’s research, New York City’s example, NACTO’s design books and classes and a few forward-thinking officials at FHWA, when the Green Lane Project started moving pebbles, a new riverbed was ready to accept the stream.

For Roskowski, it was a testament to the power of a carefully chosen, narrowly targeted campaign.

“Most advocacy tries to do a little bit for a whole lot of issues,” Roskowski said. “We had, with this, the ability to say we’re not going to spread this really thin, and we think that over time this is going to be the way to help everybody adopt this more quickly. Of course, we could only succeed because so many people worked for decades developing and pushing smart alternatives to car-centric design.?

The Green Lane Project’s model has attracted imitators. Leah Shahum, director of the Vision Zero Network, said she’d modeled her traffic-safety innovation advocacy campaign around approach she’d seen in action in the Green Lane Project focus city of San Francisco.

“We’re really taking a lesson from Green Lane playbook,” Shahum said. “We’re planning to bring together the leading cities, those who have committed to Vision Zero, to develop a similar network.”

Darryl Young, director of sustainable cities at the Summit Foundation and a partial funder of the Green Lane Project, said the project was proving a new model for policy change.

“A very limited amount of resources and a really limited amount of people can really shift not one but 10 examples across the United States,” Young said. “Five years ago, the notion of protected bike lanes was like, ‘That’s what Europeans do, are you kidding me?’ And now protected bike lanes are the norm.”

Well, almost the norm.

In 2014 Leah Golby, the Albany city councilor, got another shot at a redesign for Madison Avenue.

The Madison road diet had ended up being delayed. Now it was the first year of a new mayoral administration, and the project landed back on the city’s work plan.

But this time, when Golby started asking about protected bike lanes, she discovered an army behind her.

Albany’s local biking advocacy group, deeply opposed to the concept in 2012, had come around. Golby had begun following the Green Lane Project online and had a stream of stories from peer cities and resources to discuss with her constituents.

“There was so much out there to say ‘This is what everybody’s doing,'” she recalled.

Virginia Hammer, president of the Pine Hills Neighborhood Association and the mother of the original road diet concept, didn’t ride a bike herself. But informed by research from around the country, Hammer concluded that a comfortable biking route along Madison would boost business in a struggling district on Madison by connecting it to three more prosperous districts.

In spring 2014, Hammer, Golby and a group of other interested residents formed the Albany Protected Bike Lane Coalition.

“By the summer of 2014 we were meeting weekly,” Golby said.

An online petition for protected bike lanes on Madison drew 500 signatures in three weeks. A public rally delivered hundreds of postcards to the mayor’s office. On Park(ing) Day, the group converted two parking spots to a live demo of a protected lane.

In November 2015, the coalition presented Mayor Kathy Sheehan a 24-page full-color report, “Protected Bicycle Lanes in Albany: A Transformational Opportunity,” packed with data about the benefits of protected bike lanes and enhanced with photos that had been shot by the Green Lane Project and published in the public domain for use by local advocates.

It wasn’t quite enough for Madison Avenue. The plan would have removed 200 on-street auto parking spaces. Two weeks ago, on March 9, Mayor Sheehan said she’d decided to back a road diet with conventional bike lanes instead.

“We have people living along Madison Ave who don’t want us to do this project at all,” Sheehan explained to a reporter for All Over Albany. Conventional and protected bike lanes, Sheehan said, “were two really great choices. — That doesn’t mean protected bike lanes are dead in the city of Albany. Far from it.”

Sheehan said she’ll be looking into protected bike lanes on two other Albany streets, Broadway and Clinton Avenue, that offer a bit more width. If built, they’ll be Albany’s first protected bike lanes.

Hammer and others on the Albany Protected Bike Lane Coalition told the press they were disappointed by the lack of protection, but glad about a project expected cut crash rates on Madison by 25 percent.

United by the cause of protected bike lanes on Madison, the group now plans to continue its advocacy elsewhere in the region, with a new name: Capital Region Complete Streets.

The renamed coalition’s first meeting was last night.

Hammer told Albany’s public radio station that the fight for protected lanes on Madison had changed what Albany’s government and residents see as possible.

“It certainly put protected bike lanes on the map,” she said. “People really understand what it is now and they’re talking about it.”