Explore Our Network of Sites

Search

By:

Portland built its fame as a U.S. bike capital on one crucial discovery: It is fairly cheap and easy to make biking desirable in neighborhoods that were originally built for horses and streetcars.

This year, Oregon’s largest city will begin a new challenge: making biking desirable in a neighborhood that was originally built for cars.

The little row of shops at Northeast 102nd Avenue and Halsey Street has been on the slicing edge of transportation innovation before. When the building that’s now home to Furniture Plus was built in 1946, it anchored the first commercial district Portlanders had built for the coming age of the automobile.

“I believe it was a butcher shop in its heyday and it changed hands I don’t know how many times,” said Nidal Kahl, the building’s owner since 2010. “When I bought it, it was vacant.”

Today, Kahl’s district stands out in a city divided between painstakingly unique cafes (in its central, older neighborhoods) and generic strip malls (in its outer, newer ones). The cluster of commercial lots just south of Halsey include two sets of storefronts: the north ones facing an unbroken sidewalk, 1920s-style, and the south ones facing a two-row parking lot, 1950s style.

The Gateway District (as it’s been known for decades) is a tunnel between two worlds.

It’s the hybrid nature of Gateway’s business strip — its north face looking toward the first half of the 20th century, its south toward the second half — that has Portland’s leaders thinking these two blocks are the perfect place to begin what many of them see as the great work of the 21st century: undoing the errors of car-dependent design that began in the 1940s.

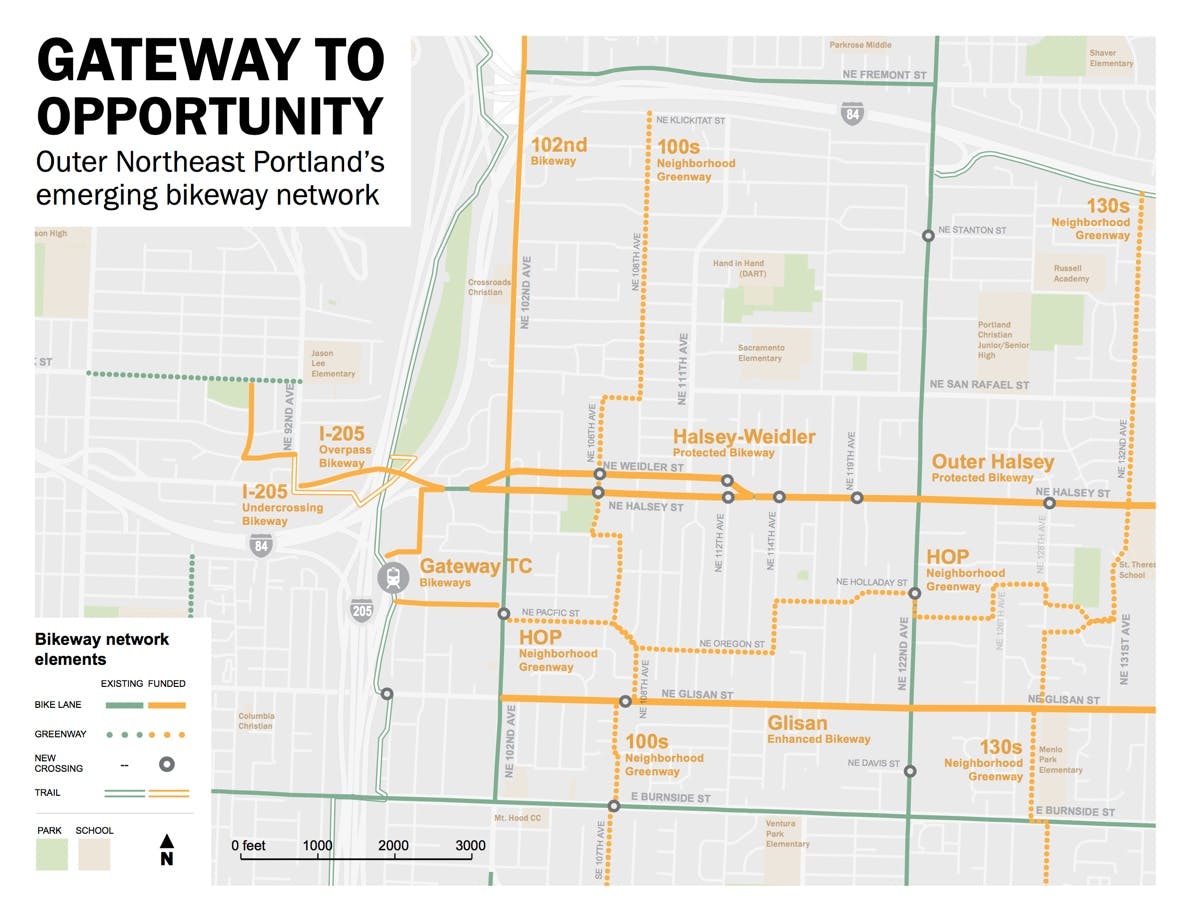

That’s why Halsey and its couplet street, Weidler, are slated for $20 million in public investment in 2018, including a major new city plaza, shorter crosswalks and parking-protected bike lanes at the hub of a new 39-mile low-stress biking network through the area.

If this row of buildings successfully leads Gateway’s transition to a more walkable, bikeable neighborhood, it’d put the street at the forefront of a national movement to redevelop close-in suburban neighborhoods.

“There’s tremendous opportunity in these kinds of places,” said June Williamson, the co-author of Retrofitting Suburbia and an architecture professor at the City College of New York. “Improving the mobility through there and the pedestrian kind of experience, allowing mobility that’s not just for cars, opens up all kinds of businesses that could be there.”

“It has the best bones of any commercial area in Gateway,” Leila Aman of Portland’s economic development office told the city council in 2016, discussing the Halsey-Weidler couplet. “And it has the potential to lift the entire district.”

“That’s going to be the most bicycle-friendly business district in all of Portland,” city bicycle planning coordinator Roger Geller said last year.

“I foresee that this corridor will become one of the greatest corridors in the city, and one that it’s most proud of,” Kahl told the council in 2016.

Here on Northeast Halsey, the sweep of history can be hard to see.

The sidewalk gets some foot traffic, mostly people heading to places like the nearby bus stops or the McDonald’s across the street.

“Most of ours is not foot traffic,” said Doug Johnson of Ollie Damon’s, a fishing and hunting supply store that operates out of the 1947 building next to Furniture Plus.

It’s not bike traffic, either. The city’s latest rush-hour bike count at 102nd and Halsey, in October 2013, observed 14 bikes in two hours. Of those 14, only eight were using Halsey’s current bike lane.

Halsey does, however, carry about 15,500 autos per day in two eastbound lanes.

The city’s plan is to preserve parking on both sides of the street, but flip the parking and bike lanes so a combination of curbs and parked cars would separate bike and auto traffic.

There’s widespread misunderstanding of that plan. Both Johnson and Omar Obeid, the manager of the furniture store in Kahl’s building, said in interviews that they thought all the parking on their side of the street would be going away.

“With the cars parked on the other side, it’d be pretty devastating for my business,” Obeid said.

The city says its plan is to clear 20 to 30 feet of auto parking — that is, one curbside space — before each intersection to provide adequate lines of sight for people turning cars across the newly protected bike lane. The sidewalks would also bulb out at intersections, shortening the distance someone has to cross the street.

Despite Obeid’s worries about parking loss, he said the streetscape project will have upsides.

“The area, it needs to be updated,” he said, saying he wished Halsey felt more like Division, Belmont or Hawthorne — onetime streetcar corridors in Portland’s booming, bikeable inner east side. “It’s an old neighborhood.”

For Arlene Kimura, a longtime advocate for investment in the Gateway area, it’s high time for a family-friendly bike network there.

“We have housing that’s cheap enough for a big family with kids,” she said. “Right now parents are absolutely terrified to have their kids ride around. When you have the protected bike lanes, it’s a whole different dynamic.”

A continuous network of low-stress bikeways that lead directly to destinations like the Gateway commercial district, David Douglas High School or the nearby Gateway Green bike park will “make a huge difference in the mobility of our kids,” she said.

“We are talking about the mobile 12- to 17-year-olds using those to get from place to place,” Kimura said. “You don’t have to ask your parents or one of your parents’ friends to drive you someplace. … The bike is the way to do it, or a combination of bike and transit.”

Kimura said that as a physically small person, she’ll be safer with the shortened crosswalks on Halsey and Weidler even though she no longer bikes herself.

“A vehicle will not see me,” she said. “Usually bike and ped connections are not exactly the same, but they provide the same benefit.”

Hanging over the project, as it does over everything in Portland in the wake of the double-digit rent hikes that followed the Great Recession’s building bust, is the risk of housing displacement.

If the bike network and sidewalk-facing business district are going to be so nice, what’s to stop people with more money from snapping up nearby homes at higher prices?

State Rep. Diego Hernandez, who represents the area, called the improved access to assets like Gateway Green “important and critical to our communities” and “long overdue.”

But continued access, he added, depends on continued affordability.

“Different urban renewal projects in the past around Portland have pushed low-income and communities of color further east or to other counties where there is more affordable housing,” Hernandez said.

Hernandez said the state’s ban on rent regulation means the city can’t stabilize rents in an area that’s seeing rapid investment. “That’s just one example of the complexity,” he said. “There are many more.”

But Hernandez also praised the Gateway investments for being shaped by deeply informed locals like Kimura.

“I think what’s really good about this Gateway project is that it was developed by folks who live in East Portland,” he said. “I come from an environmental justice background, so I always go through that lens first. Nonetheless, I’m a realist too, and I think it’ll still benefit everybody.”